A lot of the work we do at the National Institute of Agricultural Botany and Innovation Farm is about understanding and improving the genetics of different plant varieties to improve crops. We have four goals - food security, climate change, sustainability in use of resources and health, and nutrition for humans and animals.

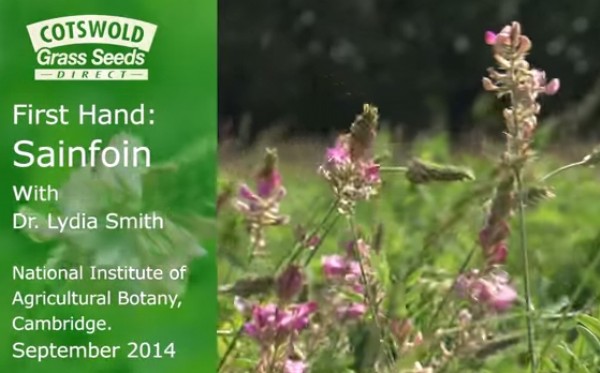

As a plant microbial ecologist, sainfoin is very close to my heart, because it fulfills all these criteria. Animals can keep eating it without any fear of getting bloat. Much more importantly, I think, is the biomedical effect of sainfoin. It helps to purge the animal of life-threatening parasitic worms and leads to better use of protein. It’s also good for the soil, being a nitrogen fixer and drought tolerant.

It was once grown all across the UK but started to disappear from farmland about 60 years ago, mainly because of the amount of biomass it produces isn’t as good as comparable legumes, like clover.

Ten years ago Prof. Irene Mueller-Harvey at Reading University, was keen to conduct research with funding by Marie Curie, focused on tannins. I was invited to represent the agricultural point of view and so we began the four-year-long Healthy Hay project, which led to the LegumePlus project and our involvement with Cotswold Seeds, one of the only companies that supply the seed to farmers.

We’ve been growing sainfoin on small scale research plots for the past five years in order to study it and find ways of improving it, testing with herbicides and companion crops, and engaging with farmers.

The numbers of farmers using this crop had gone down to tens but in the past decade that has gradually begun to creep up again. It’s wonderful to hear farmers enthusing about the rediscovery of this crop and how it could potentially help them. They notice straight away that animals fed on it immediately ‘do’ better because of the medical aspect. Sainfoin has good quality omega 3 fatty acids which impacts on metabolism, so coats immediately appear shinier.

But the problems with sainfoin are that it doesn’t respond well to herbicides and and this can lead to problems at establishment. That’s why I’m so passionate about our research. We’re exploring a range of solutions with companion crops in the establishment phase, which is throwing up interesting possibilities. We’re very excited by the results of a trial involving chicory, which prevents weeds coming in.

We’ve also been researching the genetics of sainfoin in the lab. Because sainfoin was abandoned as a crop by plant breeders and farmers very little time and effort has been put into breeding, so we’ve been bringing modern molecular methods to play. Sainfoin is hard to test, due to the high molecular weight of tannins which makes it hard to extract DNA but we’ve finally succeeded and have sequenced 5 lines, so we now have a great amount of genetic information for marker assisted breeding. This is just the start.

Date Posted: 29th March 2017